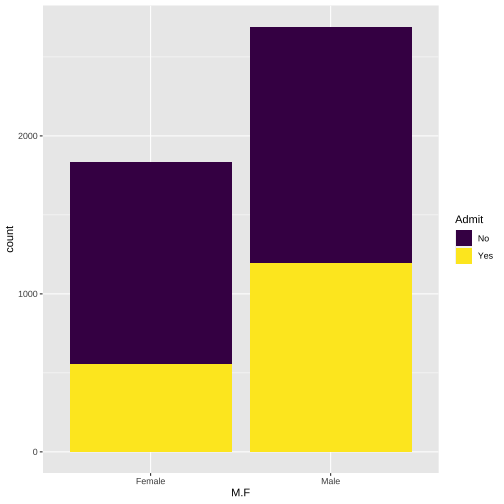

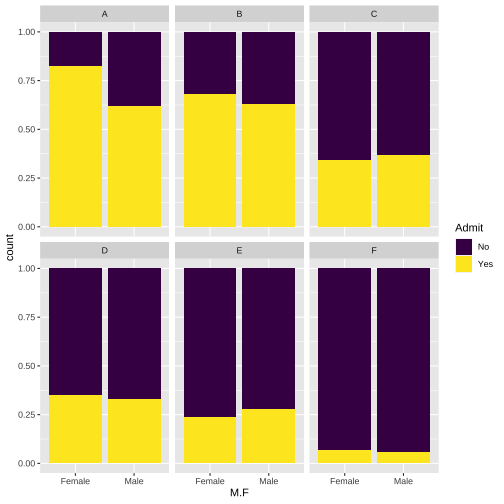

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Tidy, Probability and Tables ] .subtitle[ ## The Core of Statistical Thinking ] .author[ ### Robert W. Walker ] .institute[ ### Atkinson Graduate School of Management ] .date[ ### 2023/01/31 ] --- # Tidy thinking First, how did I import my data? ```r library(tidyverse) library(readxl) Bonds <- read_excel("probtabSMBAP21/data/Week-2.xlsx", sheet = "Bonds") CEOComp <- read_excel("probtabSMBAP21/data/Week-2.xlsx", sheet = "CEOComp") FastFood <- read_excel("probtabSMBAP21/data/Week-2.xlsx", sheet = "FastFood", na="NA") DisabilityExp <- read_excel("probtabSMBAP21/data/Week-2.xlsx", sheet = "DisabilityExp") UCBAdmit <- read_excel("probtabSMBAP21/data/Week-2.xlsx", sheet = "UCBAdmit") ``` --- # Easier ```r load(url("https://github.com/robertwwalker/DADMStuff/raw/master/Week3Data.RData")) ``` --- class: inverse, center # Probability and Tables --- class: inverse, center # Probability <!-- --> --- class: inverse # Probability .font150[ Two rules: 1. Probabilities sum to one. 2. The probability of any event is greater than or equal to zero. ] --- class: inverse # Where does Probability Come From? There are three common sources of probabilities: -- - Known formula [Dice, Coins, etc.] -- - Empirical frequency -- - Subjective belief --- class: inverse # A priori probability The probability of a given integer on a k-sided die: `\(\frac{1}{k}\)`. The probability of **heads** with a fair coin: `\(\frac{1}{2}\)`. The probability of a Queen? `\(\frac{4}{52}\)` The probability of a Diamond? `\(\frac{13}{52}\)` The Queen of Diamonds? `\(\frac{1}{52}\)` or `\((\frac{4}{52}\times\frac{13}{52})\)` **Quasirandom numbers** --- class: inverse # Empirical probability: frequency How often does something happen? <iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/tgC-vZp07YM" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" allowfullscreen></iframe> [Annie](https://youtu.be/tgC-vZp07YM) [Straight to Watch](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tgC-vZp07YM) --- class: inverse # This is Historical Statistics How likely am I to be admitted? *Consult the admissions rate* How fast do I drive? *Likelihood of law enforcement and need for speed* In data: this is tables. --- # Berkeley .pull-left[ ``` ## ## No Yes ## Female 1278 557 ## Male 1493 1198 ``` ``` ## M.F No Yes ## Female 1278 557 ## Male 1493 1198 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r library(tidyverse) library(janitor) table(UCBAdmit$M.F,UCBAdmit$Admit) UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F, Admit) ``` ] --- class:inverse # Three Versions .pull-left[ ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$M.F,UCBAdmit$Admit), 1) ``` ``` ## ## No Yes ## Female 0.6964578 0.3035422 ## Male 0.5548123 0.4451877 ``` ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$M.F,UCBAdmit$Admit), 2) ``` ``` ## ## No Yes ## Female 0.4612053 0.3173789 ## Male 0.5387947 0.6826211 ``` ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$M.F,UCBAdmit$Admit)) ``` ``` ## ## No Yes ## Female 0.2823685 0.1230667 ## Male 0.3298719 0.2646929 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F, Admit) %>% adorn_percentages("row") ``` ``` ## M.F No Yes ## Female 0.6964578 0.3035422 ## Male 0.5548123 0.4451877 ``` ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F, Admit) %>% adorn_percentages("col") ``` ``` ## M.F No Yes ## Female 0.4612053 0.3173789 ## Male 0.5387947 0.6826211 ``` ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F, Admit) %>% adorn_percentages("all") ``` ``` ## M.F No Yes ## Female 0.2823685 0.1230667 ## Male 0.3298719 0.2646929 ``` ] --- background-image: url("UCBM.png") background-size: contain class: bottom # Plot It ```r ( UCBM <- ggplot(UCBAdmit) + aes(x=M.F, fill=Admit) + geom_bar(position="dodge") + scale_fill_viridis_d() ) ``` More on this later. --- class: inverse # Subjective Probability How likely **do we believe** something is? --- class: inverse # The Great Divide Empirical frequency vs. subjective belief --- class: inverse # Empirical Frequency: She's Right ## Physics Disagrees: We Goin Nova..... -- ## Annie's a liar. What matters in group decision making is probably as much the beliefs [subjective] as the evidence [frequency]. How should we reflect this in strategies of argumentation/persuasion? --- class: inverse ```r # RUN ME # may need to install.packages("countdown") library(countdown) countdown_fullscreen( minutes = 5, seconds = 0, margin = "5%", font_size = "8em", ) ``` <div class="countdown countdown-fullscreen" id="timer_32ff2890" data-update-every="1" tabindex="0" style="top:0;right:0;bottom:0;left:0;margin:5%;padding:0;font-size:8em;"> <div class="countdown-controls"><button class="countdown-bump-down">−</button><button class="countdown-bump-up">+</button></div> <code class="countdown-time"><span class="countdown-digits minutes">05</span><span class="countdown-digits colon">:</span><span class="countdown-digits seconds">00</span></code> </div> --- # Three Concepts from Set Theory - Intersection [and] - Union [or] **avoid double counting the intersection** - Complement [not] --- # Three Distinct Probabilities - Joint: Pr(x=x and y=y) - Marginal: Pr(x=x) or Pr(y=y) - Conditional: Pr(x=x | y=y) or Pr(y =y | x = x) --- # Joint Probability **The table sums to one**. For Berkeley: ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F, Admit) %>% adorn_percentages("all") ``` ``` ## M.F No Yes ## Female 0.2823685 0.1230667 ## Male 0.3298719 0.2646929 ``` ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$M.F,UCBAdmit$Admit)) ``` ``` ## ## No Yes ## Female 0.2823685 0.1230667 ## Male 0.3298719 0.2646929 ``` --- # Marginal Probability **The row/column sums to one**. We collapse the table to a single margin. Here, two can be identified. The probability of Admit and the probability of M.F. .pull-left[ ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F) ``` ``` ## M.F n percent ## Female 1835 0.4054353 ## Male 2691 0.5945647 ``` ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(Admit) ``` ``` ## Admit n percent ## No 2771 0.6122404 ## Yes 1755 0.3877596 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$M.F)) ``` ``` ## ## Female Male ## 0.4054353 0.5945647 ``` ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$Admit)) ``` ``` ## ## No Yes ## 0.6122404 0.3877596 ``` ] --- # Conditional Probability How does one margin of the table break down given values of another? **Each row or column sums to one** Four can be identified, the probability of admission/rejection for Male, for Female; the probability of male or female for admits/rejects. For Berkeley: .pull-left[ ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F, Admit) %>% adorn_percentages("row") ``` ``` ## M.F No Yes ## Female 0.6964578 0.3035422 ## Male 0.5548123 0.4451877 ``` ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$M.F,UCBAdmit$Admit), 1) ``` ``` ## ## No Yes ## Female 0.6964578 0.3035422 ## Male 0.5548123 0.4451877 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r UCBAdmit %>% tabyl(M.F, Admit) %>% adorn_percentages("col") ``` ``` ## M.F No Yes ## Female 0.4612053 0.3173789 ## Male 0.5387947 0.6826211 ``` ```r prop.table(table(UCBAdmit$M.F,UCBAdmit$Admit), 2) ``` ``` ## ## No Yes ## Female 0.4612053 0.3173789 ## Male 0.5387947 0.6826211 ``` ] --- # Law of Total Probability Is a combination of the distributive property of multiplication and the fact that probabilities sum to one. For example, the probability of Admitted and Male is the probability of admission for males times the probability of male. $$ Pr(x=x, y=y) = Pr(y | x)Pr(x) $$ Or it is the probability of being admitted times the probabilty of being male among admits. $$ Pr(x=x, y=y) = Pr(x | y)Pr(y) $$ --- # Now the Substance .pull-left[ The `ggplot` fill aesthetic is great for displaying these things. For example, are males and females equally likely to be admitted to Berkeley? **Plaintiffs say no.** ```r ggplot(UCBAdmit) + aes(x=M.F, fill=Admit) + geom_bar() + scale_fill_viridis_d() ``` ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # Is that an Adequate Comparison? .pull-left[ The University says no. Why? The most important factor in the probability of admission is likely to be the department. This has a huge impact on what we see. ```r ggplot(UCBAdmit) + aes(x=M.F, fill=Admit) + geom_bar(position="fill") + scale_fill_viridis_d() + facet_wrap(vars(Dept)) ``` ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # The Magic of Bayes Rule To find the joint probability [the intersection] of x and y, we can use either of the aforementioned methods. To turn this into a conditional probability, we simply take it is a proportion of the relevant margin. $$ Pr(x | y) = \frac{Pr(y | x) Pr(x)}{Pr(y)} $$ By itself, this is algebra. It is magic in an application. $$ Pr(User | +) = \frac{Pr(+ | User) Pr(User)}{Pr(+)} $$ This poses the question: what does a positive test mean? --- # Working an Example Suppose a test is 99% accurate for Users and 95% accurate for non-Users. Moreover, suppose that Users make up 10% of the population. So given some population to which this applies, we have: `\(Pr(User, +) = Pr(+ | User)*Pr(User)\)` `\(Pr(User, -) = Pr(- | User)*Pr(User)\)` `\(Pr(\overline{User}, +) = Pr(+ | \overline{User})*Pr(\overline{User})\)` and `\(Pr(\overline{User}, -) = Pr(- | \overline{User})*Pr(\overline{User})\)` --- ## The Table Status | Positive | Negative | Total ---------|-----------|----------|------ User | 0.099 | 0.001 | 0.1 non-User | 0.045 | 0.855 | 0.9 ---------|-----------|----------|------ Total | 0.144 | 0.856 | 1.0 `\(Pr(User | +) = \frac{Pr(+ | User) Pr(User)}{Pr(+)}\)` yields: `\(Pr(User | +) = \frac{0.099 [0.99*0.1]}{0.144[0.99*0.1 + 0.05*0.9]} = 0.6875\)` why? 10% of users with 99% accuracy given users should yield 0.099 [0.99 times 0.1] positive and 0.001 [0.1 times 0.01] negative. Similar, 90% non-users with 95% accuracy yields negative with probability 0.855 [0.95 times 0.9] and positive for the rest [0.05 times 0.9]. --- # Dichotomization is Prone to Error As Jaynes suggests, probability is the extension of Aristotellian logic, but we are often trying to go back to binary in making decisions. Characterizing both forms of decision error, whether called false positives and false negatives, sensitivity and specificity, or Type-I and Type-II errors becomes of paramount importance. --- # A Bit of Decision Theory Juries